|

|

Post by groundhog on Aug 26, 2012 23:10:53 GMT

The Battle of Castlebar

27th August 1798 The long overdue French landing to assist the 1798 rebellion took place on 22nd August 1798. General Jean Joseph Humbert landed at Cill Chuimín Strand, County Mayo with almost 1,100 men and proclaimed the formation of the Republic of Connaught. The landing was unopposed because all the government forces were concentrated in Leinster, the focus of the 1798 rebellion. The French quickly captured Killala after a brief resistance by the local yeomanry and Ballina was taken on the 24th. Following the news of the French landing, Irish volunteers began to trickle into the French camp from all over Mayo. The Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Cornwallis, concentrated all available forces at Castlebar under the command of General Gerard Lake. Lake had been the commander at Vinegar Hill in June. By the morning of 27th August the British forces at Castlebar had reached 6,000 soldiers with artillery and plentiful supplies. Humbert left 200 French soldiers in Killala to cover his line of withdrawal and advanced on Castlebar on August 26th with a combined force of about 2,000 French troops and Irish rebels. Lake assumed that Humbert would advance along the Ballina road and he deployed his forces to cover the expected French advance from that direction. However, local rebels had told Humbert of an alternative route to Castlebar along the west shore of Lough Conn, a route the British thought impassable for a conventional force. When Lake’s scouts spotted the approaching enemy, the surprised British had to hurriedly change their deployment to face the new threat. The British had just completed redeploying their troops when the Franco-Irish army appeared outside Castlebar at 6 am. The British artillery immediately opened up on the advancing French and Irish and cut them down in substantial numbers. However as luck would have it in front of the British line was a gully which allowed an approach to the British position under cover. From here the French launched a bayonet charge. Behind the artillery was the British infantry line made up mostly of militia units. Unnerved by the French charge the infantry broke and ran in both directions. Some of the Longford and Kilkenny militia ran to join the rebels. The fleeing troops overwhelmed a unit of cavalry and British regular infantry who attempted to stand and stem the tide. The French broke off the pursuit a mile or two beyond Castlebar, but the broken troops continued to flee, some as far as Tuam and Athlone. Massive quantities of guns and equipment were abandoned, including General Lake’s personal luggage. The rout has gone down in Irish history as the Races of Castlebar. The Franco-Irish lost about 150 men in the battle, mostly to the British artillery. The government side lost 350, including 150 defectors and 80 killed. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Aug 27, 2012 11:51:55 GMT

The Warrenpoint Ambush

27th August 1979  An aerial view of the ambush site from The Newry TimesThe Warrenpoint Ambush took place on 27th August 1979. It is unlikely that it was planned as retaliation for the Bloody Sunday killings which had occurred almost eight years previously. However it was retrospectively seen by Republicans as fitting revenge since most of the casualties were members of the Parachute Regt. A common piece of graffiti at the time was "Thirteen dead but not forgotten, we got eighteen and Mountbatten." Lord Mountbatten had been killed earlier the same day by an IRA bomb in Sligo. The ambush began when a convoy consisting of 4 trucks and a Land rover of A Coy, 2nd Bn, The Parachute Regt, was hit by a 500lb bomb concealed in a trailer of hay bales near Narrowwater Castle, Co. Down at 1640 hrs. The rear truck in the convoy was destroyed and six soldiers killed. Assuming they were being ambushed, the surviving soldiers opened fire killing one civilian, an Englishman named Michael Hudson, and wounding another. When reports were received of the explosion reinforcements were sent by 2 Para by road. A rapid reaction force was sent by helicopter consisting of medical staff and engineers and Lt Col Blair, CO of the Queen's Own Highlanders flew in to take command of the scene. Blair set up his Incident Command Point in the gate of Narrowwater Castle. The IRA had planted another bomb here in the gate lodge and this was detonated at 1712 hrs, killing 12 more soldiers including Lt Col. Blair and his signaller L/Cpl Victor McLeod. Two men suspected of participating in the ambush were arrested by the Gardai in the Republic but subsequently released. Warrenpoint was the heaviest loss of life in one incident for the British Army in Northern Ireland. Fatal casualty list

Lt-Col David Blair, Queen's Own Highlanders

Maj Peter Fursman, 2 Para

Warrant Officer Walter Beard, 2 Para

Sgt Ian Rogers, 2 Para

Cpl Nicholas Andrews, 2 Para

Cpl John Giles, 2 Para

Cpl Leonard Jones, 2 Para

L/Cpl Victor McLeod, Queen's Own Highlanders

L/Cpl Chris Ireland, 2 Para

Pte Gary Barnes, 2 Para

Pte Donald Blair, 2 Para

Pte Raymond Dunn, 2 Para

Pte Anthony Wood, 2 Para

Pte Michael Woods, 2 Para

Pte Thomas Vance, 2 Para

Pte Robert England, 2 Para

Pte Jeffrey Jones, 2 Para

Pte Robert Jones, 2 Para |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Sept 7, 2012 10:38:44 GMT

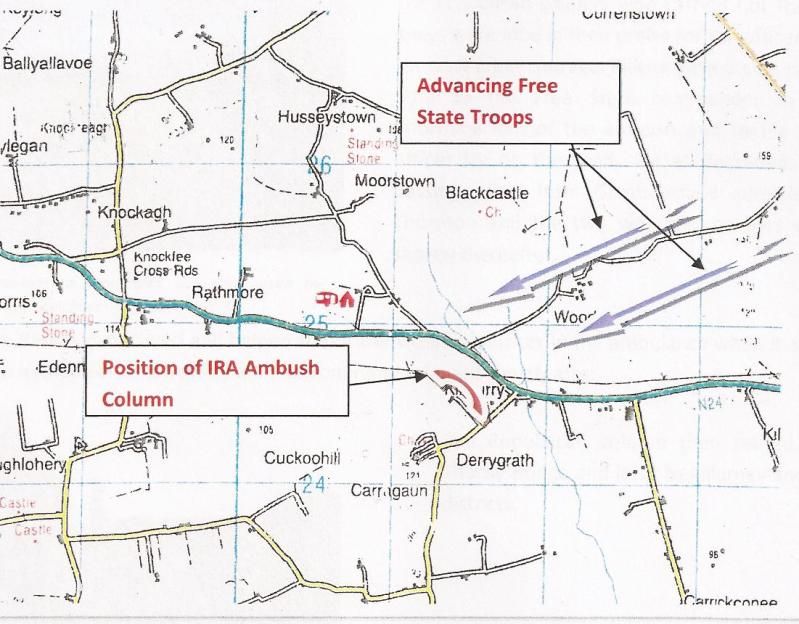

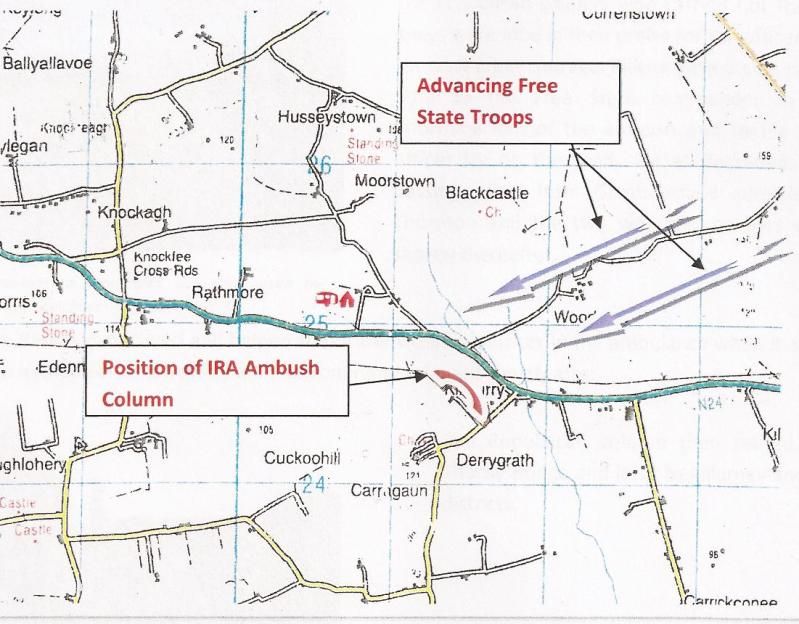

THE DERRYGRATH AMBUSHES In the autumn of 1922 one of the most dangerous places in Ireland was the main road from Clonmel to Cahir in Co.Tipperary. Two ambushes took place at Derrygrath in the space of three weeks in August/September 1922. The First Ambush

16th August 1922 After the fall of Clonmel on August 9th 1922, the IRA units in the area of south Tipperary divided into two Flying Columns and reverted to the guerilla tactics that had been so successful in the War of Independence. No 2 Flying Column with a strength of 70 men was commanded by Jack Killeen. Its armament was Lee-Enfield Rifles, pistols and two Lewis Machine Guns.  Killeen's Column in July 1922. Killeen is standing by the lorry Killeen decided to ambush one of the regular patrols that ran between Clonmel and Cahir. On 16th August he deployed his Column at Derrygrath on high ground overlooking the road. After blocking the road the men of the column took firing positions along a lane leading to a farm. A patrol under a Capt. Mullaney left Clonmel that morning but instead of driving directly to Cahir the men deployed out of their transport and moved cross-country north of the road through the Woodroffe estate, swinging south to meet their transport again at the gates to Woodroffe demesne. At that time a small church stood at the site. By ill-luck the RV was at the ambush site and the IRA Column opened fire on the Free State soldiers as they boarded their trucks. The soldiers took cover in the ditches along the road and a fire fight commenced that lasted an hour until the Column withdrew south leaving three National Army soldiers dead and nine wounded. The three KIA were; Cpl Fogarty, Templemore, Co. Tipperary Pte Bergin, Catlecomer, Co. Kilkenny Pte Roche, Cahir, Co. Tipperary The Second Ambush

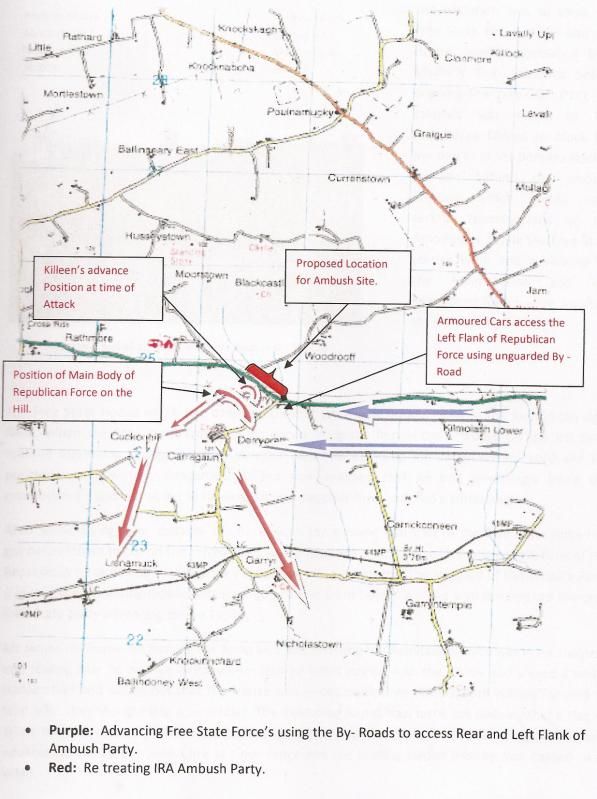

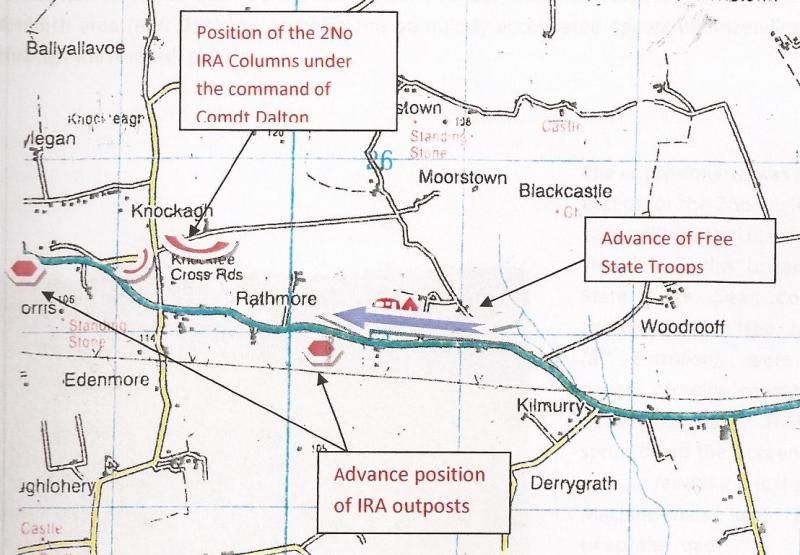

7th September 1922 On the 7th September Killeen decided to once again set up an ambush at Derrygrath in the same place as the one three weeks before. The column must have been getting cocky however because it almost cost them dearly. As they were setting up the ambush they were spotted by a Free State patrol at Barne nearer Clonmel. This patrol returned to report and a stronger patrol was sent out accompanied by two Armoured Cars. Word was also sent to Cahir Barracks whence another patrol departed for the ambush site. The intention was for the two Free State Patrols to surround and capture or kill all members of Killeen’s Column. The Armoured Cars moved along the road while men on foot spread out in extended lines and moved cross country towards the IRA column. As well as moving into position in broad daylight, Killeen had also neglected to put out sentries at his flanks and rear. The side roads leading to the ambush site were also left unblocked. Killeen himself with a small group of men was down on the main road near Woodroffe church when the Free State soldiers opened fire on his men on the hill. Almost simultaneously the Armoured Cars arrived and turned into the by-road leading to the farm on the hill. Killeen ordered a withdrawal. Within a short time however the IRA men realised that there were Free State troops in their rear. What had been the left flank of the ambush was forced westwards to Cuckoohill. Here they took cover in Heffernan’s farmyard. When the Free State soldiers came into range they opened fire. Heffernan unaware that his farm was now a battlefield waved a white flag from a window. The National Army soldiers, assuming that the Republicans were giving in, moved forward to take the surrender and were fired upon. Pte John Hanley from Cashel was killed here. Hanley was a First World War veteran. One brother had died on the Somme and another had lost a leg in France. In the confusion the men of the Column crawled down a dry ditch and escaped the encircling Free State Forces. The remainder of the Column was left with a fighting retreat for two hours until they managed to break contact and RV at Lisnamuck. The IRA Column had suffered no fatalities in the fighting. On the Free State side, apart from the dead soldier, Comdt Tommy Ryan was wounded but recovered. The decision by Killeen to carry out an ambush at the same location so soon after the first ambush as well as his failure to put out sentries and cover his rear almost led to disaster for his Column. He waslucky that the Free State Forces did not manage to surround the IRA men fully before opening fire. Jack Killeen was captured by the National Army a week later and his place as leader of No 2 Column was taken by Comdt Paddy Dalton from Donohill. Thanks to Paul Cremmins for the maps |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Sept 10, 2012 0:05:16 GMT

The Battle of Connor

Co. Antrim

10th September 1315 Also called the Battle Tawnybrack, It was fought a few miles south of Ballymena, Co. Antrim on September 10th 1315. The most poweful of the Anglo-Irish nobles was Richard de Burgo the Red earl of Ulster. He raised a large army, mainly in Connaught which was the de Burgo or Burke home territory, to expel Bruce from Ireland. His march north through the Irish districts was as savagely destructive as that of Bruce further to the east. Along with him De Burgo brought several Irish chieftains and their followers one of whom was Phelim O'Connor the king of Connaught. While Phelim was away one of his relatives seized the throne and O’Connor had to return home to restore order. De Burgo’s force, weakened by the defection of O'Connor, was attacked by Bruce’s Army near Ballymena and defeated. Little is known about the details of the battle of Connor other than who won. De Burgo had about 6,000 men. After the battle he led most of the survivors, back to Connaught, while some others made their way to join the garrison of the besieged Carrickfergus Castle which was under siege for a year before it fell. De Burgo’s brother was captured at Connor. For a background to the Bruce Wars; stmhs.proboards.com/index.cgi?board=general&action=display&thread=25&page=1#ixzz261DVvhcv |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Sept 10, 2012 23:01:15 GMT

The siege of Drogheda

Co. Louth

11th September 1647 The siege took place during the Cromwellian Campaign in the second week of September 1649. Having landed in Ireland in August, to re-conquer the country on behalf of the English Parliament, Oliver Cromwell moved north to Drogheda in September. The town was garrisoned by an English Royalist regiment under Col Arthur Aston and Irish Confederate troops. The garrison had a total strength of about 3100 men, roughly half English, half Irish. Cromwell had around 12,000 men at Drogheda and eleven 48-pounder artillery pieces. Cromwell however didn’t want to go through the lengthy process of blockading the town and forcing a surrender so he opted for a direct assault. He positioned his forces on the south side of the river Boyne concentrated for an attack. On Monday 10th September Cromwell had a letter delivered to Aston, calling him to surrender the town. Aston refused so Cromwell ordered his artillery to begin the bombardment of the town. The Parliamentarian batteries were situated on the south side of Drogheda. The first battery was aimed at the southern wall between the Duleek Gate and St Mary's Church, whose tower was used as an observation post by the Royalists. The second battery was placed to the east of St Mary's to fire across a ravine which ran along the eastern wall. The batteries were placed so that the breaches they made would allow the two columns of assault troops to converge in the south-eastern corner of the town and mutually support one another once they had gained entry. Aston ordered the construction of additional defensive earthworks when he realised where Cromwell intended to concentrate his fire. The cannon quickly battered two large breaches in the town's medieval walls and Cromwell ordered his troops to assault the breaches at 5 pm on September 11th. The regiments of Colonel Castle and Colonel Ewer attacked the southern breach while Colonel Hewson's regiment drew the short straw and had to attack across the ravine and into the eastern breach. Hewson's men met with fierce resistance in the eastern breach. Their first assault was thrown back and they began to retreat back down the ravine. The regiments of Colonel Venables and Colonel Phayre came up in support and the Parliamentarians succeeded in forcing their way into the town. The assault on the southern breach also met with heavy resistance. Colonel Castle was shot in the head and killed during a Royalist counter-attack and his men began to retreat. Cromwell himself moved into the breach to rally the wavering men. At this stage the tide turned and the Royalist commander in the breach, Colonel Wall was killed. The defenders fell back as the Parliamentarians poured through the breaches and overran the Royalist defences. The soldiers of the New Model Army pursued the defenders through the streets, killing them as they ran. Aston and about 200 men barricaded themselves into Millmount Fort, which overlooked the town's eastern gate. This fort held out while the rest of the town was being sacked but eventually it too fell and the defenders were put to the sword. Aston was reputedly beaten to death with his own wooden leg when the Parliamentarians took the Mill Mount.Another group of soldiers holed up in St Peter’s church, at the northern end of Drogheda. They were burned to death when the Parliamentarian soldiers set fire to the Church. About 200 of the garrison survived the assault on Drogheda. They were transported as slaves to Barbados, which for Europeans in the 17th century was as good as a death sentence. Estimates of civilian casualties vary from several hundred to several thousand. In Irish history the siege has gone down as a Cromwellian massacre, making Oliver one of the most hated men in history. 150 Parliamentarians died in the assault. After the fall of Drogheda, the Royalists abandoned the towns of Trim and Dundalk without a fight. Cromwell sent three regiments under Colonel Venables north to join forces with Sir Charles Coote in Ulster while he returned to Dublin with the main body of his army and prepared to advance into southern Ireland. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Sept 11, 2012 23:00:27 GMT

The Sack of Cashel

Co. Tipperary

12th September 1647  The Rock of Cashel The Rock of CashelThe Sack of Cashel was part of the Confederate Wars. I’m unsure about the actual date, it varies from 12th to 15th September. Much of Munster had been ruled by the Confederation of Kilkenny since 1642, only Cork and some town along the coast remaining under Parliament control. In the summer of 1647 a Parliamentary Force commanded by Murrough O’Brien, Lord Inchquin, raided into Confederate territory. They took Cahir Castle in early September and Inchiquin decided to launch an attack on the town of Cashel. Both towns commanded the route out of Munster to Dublin. In Cashel, the Confederate Commander in Munster, Lord Taaffe, had left as Governor one Lt-Col Butler and a small force of 600 troops. These garrisoned the Rock of Cashel which, while relatively well fortified, was more a medieval church than a fort. It had a perimeter wall and was situated atop a steep sided limestone outcrop above the surroundinng countryside. Inchiquin’s men took an outlying fort called Roche Castle and then entered the town, which had been abandoned by the populace. Arriving before the Rock he demanded the surrender of the garrison within an hour. This was refused and the assault began There was no finesse, Inchiquin imply formed a column of his men led by 150 Dragoons and they simply climbed over the wall while the soldiers inside tried to fight them off with pikes and the civilians threw rocks down on them. Some buildings were fired inside the walls and the garrison retreated inside the Church. An attempt by Inchquin’s troops to break through the doors failed, but the attackers brought up ladders and swarmed through the windows. A melee inside the church for thirty minutes ended with the 60 or so survivors retreating into a bell tower. When called on to surrender, they complied only to be slaughtered once they were disarmed. Of the garrison only one soldier survived the attack and most of the civilians were also killed. The Church was ransacked and the town burned. An estimated 1,000 people died in the massacre. The sack of Cashel had little strategic impact though it did widen a split in the Confederacy between the Catholics and the Royalists. A desire for revenge led to the Munster Army under Taaffe ill-adviedly seeking battle with Inchquin at Knocknanuss in November. But that’s another story. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Sept 19, 2012 23:01:57 GMT

The Battle of the Moyry Pass

Co. Louth

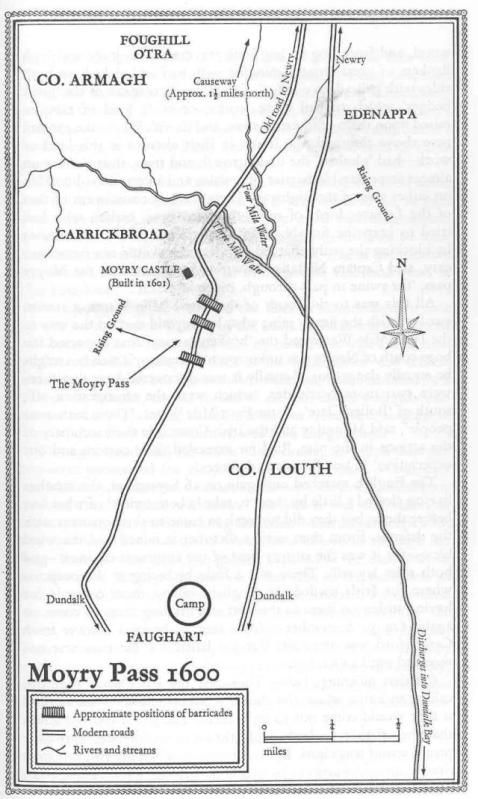

20th September-9th October 1600 A battle fought as part of the Nine Years War. It began on September 20th 1600 and was fought intermittently until 9th October. Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, had been appointed Lord Deputy of Ireland in 1600, with the task of bringing the Irish rebellion to an end. With this in mind he first landed forces from the sea at Derry in the north and Carrickfergus in the east and then began an overland invasion of the O'Neill lands in central and western Ulster. The shortest way to Ulster was through the Moyry pass on the road from Dundalk to Newry and Armagh. Early in September Mountjoy moved from Dublin to Dundalk with the intention of re-establishing a garrison in Armagh, evacuated after the Yellow Ford two years previously. On 17th September Mountjoy marched from Dundalk towards the Moyry Pass which had been fortified by O'Neill with trenches and barricades. The Irish had constructed three lines of trenches, backed up with barricades of earth and stone in the pass and on the flanks had made further earth and stone works to provide cover for themselves and prevent the English occupying the heights on either side of the Pass. In these positions, they awaited the English assault. The English force reached the pass on 20th September and set up camp at the southern entrance on Faughart Hill. On the 25th, an officer named Thomas Williams (who had commanded the Blackwater Fort during the Battle of the Yellow Ford) made a sortie into the pass, under cover of a heavy mist. He found the Irish defensive works and engaged in a skirmish before returning to camp having suffered 12 dead and 30 wounded. Heavy rain prevented fighting for the next week, until the weather cleared on 2nd October, when Sir Samuel Bagnall led his regiment of infantry into the Pass followed by four other regiments. Bagnall’s men breached the first barricade and then Thomas Bourke's regiment took over the attack on the second and third lines of defence. Once the second line was crossed the English troops found themselves trapped under fire from three sides. For three hours they tried to dislodge the Irish from their remaining positions before retreating with the loss of at least 46 killed and 120 wounded. On 5th October, Mountjoy tried unsuccessfully to bypass Moyry by sending two regiments over the hills to the west of the Pass. In addition he sent a regiment supported by horsemen into the Pass. Again this force was thrown back with reported losses of 50 dead and 200 wounded. Mountjoy retired to Dundalk on the 8th of October. However, on the 14th, he received word that O'Neill had abandoned the Pass and retreated to Lough Lurcan. O'Neill's withdrawal was probably due to a shortage of ammunition and food and fear of an attack on his rear from Newry. Mountjoy marched into Moyry Pass unopposed on the 17th of October and dismantled the Irish earthworks. He then marched on to Carrickban, outside Newry. After a stay at Carrickban, Mountjoy marched to Mountnorris, which he reached on Sunday 2nd November. There he built an earthwork fort garrisoned by 400 men under the command of Captain Edward Blaney. Returning to Newry from Mountnorris, the English marched back to Dundalk via Carlingford. On 13th November, during this return march they were again attacked by O'Neill, close to the Fathom Pass, losing 20 men killed and 60 to 80 wounded. Mountjoy claimed to have lost 200 men killed and 400 wounded in the battle for Moyry Pass as well as claiming to have killed over a thousand Irish. Historians think he dramatically understated his own losses and inflated those of O’Neill. Moyry Pass has frequently been a strategic site in Irish history. Edward Bruce was killed there in 1318 and the Jacobites and Williamites fought a short battle there in 1690 before the Boyne. Map Credit; britishbattles.homestead.com/ireland2.html |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Sept 23, 2012 22:23:50 GMT

The Battle of Ardnaree

Co. Mayo

23rd September 1586 [/b] The Battle of Ardnaree was fought as part of the Tudor Conquest of Ireland. On the one hand were the Old English lords of Connacht- the Burkes and the Irish MacPhilbins. On the other were the new English settlers led by Sir Richard Bingham, Governor of Connacht. The Burkes had hired in Irish and Scottish mercenaries under the MacDonald brothers- Alexander Carragh MacDonald and Donald Gorm MacDonald who had land on both sides of the North Channel. The mercenary army numbering about 2,000 pushed through Sligo into Mayo and camped on the banks of the River Moy near Ballina. The campsite is now part of the town. On the night of the 22nd/23rd September, Bingham surrounded the camp and attacked in the morning, slaughtering all that were found there. The two brothers MacDonald died in the attack. Bingham went on to rout the Burkes, hang their leaders and confiscate their land. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Oct 1, 2012 23:13:17 GMT

Mollsheens Cross Ambush

Co. Tipperary

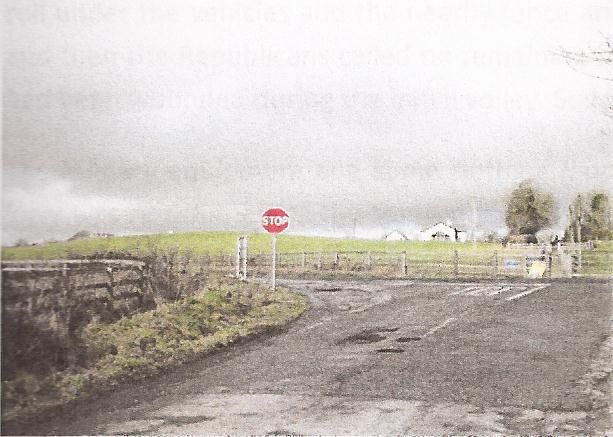

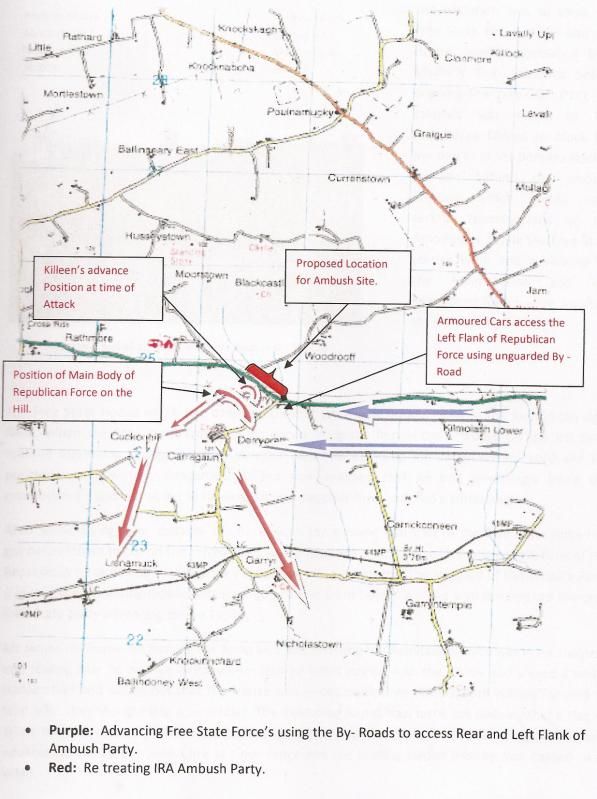

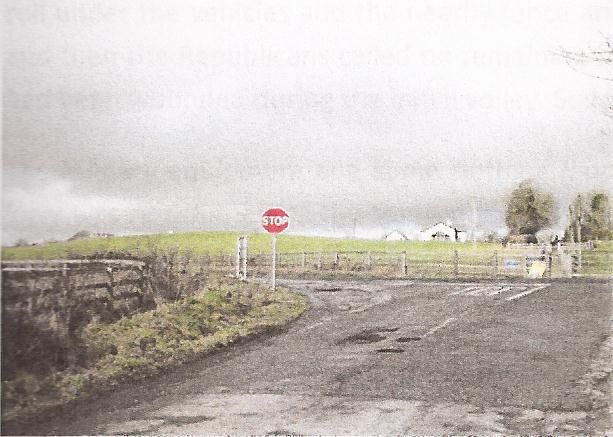

2nd October 1922 [/b] In August and September you’ll recall, No 2 Flying Column, 3rd Tipperary Bde carried out two ambushes on National Army troops travelling from Clonmel to Cahir, at Derrygrath. On 2nd October 1922 they tried again at a site about a mile closer to Cahir. A Cork Column was in the area of Araglen on the Cork/Waterford border and with Free State forces moving into the area, it was thought that troops from Clonmel would be involved. It was decided to set up an ambush at a place called Mollsheens Cross 1 on any troops moving from Clonmel through Cahir to Araglen.   Paddy Dalton OC Column & Jim Nugent IC No 1 Section The Flying Column was now commanded by Comdt Paddy Dalton from Donohill, Co. Tipperary. Jack Killeen, the previous OC, had been captured on September 14th near Kilcash. The Column was billeted at Ballybacon on the night of 1st October while Comdt Dalton, Lt Sean Cooney 2 and Jack Lonergan went to recce the ambush site in the evening. It was decided to place the ambush party on the high ground about 100m north of the main road, with two mines planted in the roadway. The engineering party to plant the mines moved out before the main body as they were to have the devices in position before the main body arrived. Twelve men went with the engineers and this party split up and deployed east and west of the ambush site to warn of the approach of National Army Patrols. The mine was planted at dawn and the main ambush party then arrived and set up positions, one section under Jim “The Gunner” Nugent on the left flank covering the main road and a second section, under Jack Aylward, on the right flank and facing towards Clonmel. (See Map). Once the ambush was in position Sean Cooney and Ned McNamara went onto the road to connect the firing cables to the mines. As they were doing so, warning shots were heard coming from the Clonmel direction and a single Crossley Tender full of troops came into view. Cooney and McNamara sprinted down the side road to cover in a derelict house. As they reached the house the ambush party opened fire with rifles and Lewis guns on the Free State lorry.  The ambush site today. The ambushers were located on the hill. Sean Cooney and Ned McNamara ran down the road towards the camera to take cover. The initial burst of fire wounded a number of the troops in the lorry, including the driver, who lost control of the vehicle. As the troops de-bussed, the Commanding Officer Capt Joseph Walsh was hit in the head and died. Nugent led his section down the hill in an attack on the survivors who quickly surrendered. The ambush party took whatever equipment they could carry from the Free State soldiers and withdrew south to Newcastle. The Republican Column had suffered no casualties in the ambush while on the National Army side, Capt Joseph Walsh from Mullinahone had been KIA and Pte Thomas Brownrigg from Dunmore, Co. Kilkenny died of wounds the following day. Five other soldiers were wounded in the attack. Paddy Dalton was killed in Donohill on October 26th. Photo Credits; Map & photo of ambush site by Paul Cremmins Notes 1. The Cross roads was officially called Knockfee Cross. Due to reconstruction of the roads in the area, it is no longer a cross roads but a T-Junction. 2.There was another Sean Cooney who was a National Army Officer in Clonmel at this time. The two were not related. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Oct 11, 2012 8:27:18 GMT

The Fall of Wexford

Co. Wexford

11th October 1649 [/b] After the fall of Drogheda, the Royalist army under the Marquis of Ormond withdrew from most of Leinster. Ormond retreated to Kilkenny with his remaining forces, abandoning Trim and Dundalk. Cromwell, with Dublin secure, turned south while Colonel Venables advanced into Ulster. Cromwell wanted to capture the southern ports before the onset of winter in order to cut the Royalist lines of communication with France and Spain. Cromwell's first objective was Wexford, a major port and a base for privateering raids on English shipping. Cromwell left Dublin on 23rd September and marched down the coast. A support fleet of twenty ships under the command of General-at-Sea Richard Deane shadowed his march with supplies and siege artillery. Cromwell's army was now reduced to 9,000 men, three regiments accompanying Venables into Ulster and garrisons having been posted in Dublin and Drogheda. Apart from a Confederate raid south of Arklow, the Parliamentarians met with no resistance on the march south. Royalist garrisons at Arklow, Ferns and Enniscorthy surrendered and the Cromwell’s army arrived at Wexford on 1st October 1649. Ormond had reinforced the garrison of Wexford with 1,000 men under the command of Colonel David Sinnott. A force also moved from Kilkenny to New Ross in order to protect Wexford's supply lines. Wexford is situated on the south side of the River Slaney. Its harbour is sheltered by two fingers of land to the north and south and at that time it was guarded by Rosslare Fort on the southern side. Cromwell crossed the Slaney at Enniscorthy and approached Wexford from the south. The speed of his advance took the garrison of Wexford by surprise and the Rosslare garrison, unprepared for an attack, abandoned the fort on 2nd October. Lt-Gen Michael Jones (recently rampging around Dublin and Rathmines) captured the fort without firing a shot. With Rosslare in Parliamentarian hands, Cromwell's support fleet was able to enter Wexford Bay in safety and unload the siege artillery on the south side of the town. Cromwell set up his batteries to concentrate their fire on Wexford Castle which dominated the south-eastern corner of the defences and which overlooked part of the town wall. With his forces in place, Cromwell demanded the surrender of Wexford on 3rd October, offering lenient terms in the hope that he could secure the town intact and use it as winter quarters for his troops. The citizens of the town were anxious to surrender but Sinnott played for time. He knew that a winter siege would be hard on the Parliamentarians and that disease and exposure would lift the siege and fatally weaken Cromwell’s army. Meanwhile Ormond sent another 1,000 infantrymen to Wexford to strengthen the garrison. One drawback for the Royalists was the fall of Youghal when the Protestants of the town declared for Parliament. Ormond sent Lord Inchiquin with a regiment of cavalry to reoccupy the town, weakening his army at New Ross. Meanwhile negotiations between Cromwell and Sinnott continued until 10th October at which point Cromwell's patience ran out and he ordered his artillery to begin bombarding the walls of Wexford Castle. The following day, Sinnott agreed to accept Cromwell's terms, by which the soldiers of the garrison would be disarmed and allowed to march away, the officers would become prisoners and the town would not be plundered. A delegation was sent to meet Cromwell to finalise the surrender. This delegation presented a further set of proposals to him for negotiation. seeking protection of the town's Catholic clergy, that the garrison be allowed to withdraw to New Ross with all their weapons and ammunition and that the privateers of Wexford could sail away with their goods and ships intact. Cromwell refused and negotiations broke down. All the while the Parliamentarian artillery continued to bombard Wexford Castle. By the afternoon of 11th, the guns had succeeded in opening two wide breaches in the castle wall. The commander of the castle, a Captain Stafford, agreed to surrender before an assault could be launched. Cromwell's troops occupied the castle battlements and turned its guns on the town whereupon, the Royalists guarding the south wall fled. The Parliamentarians launched an immediate attack, scaling the abandoned walls, opening the gates and storming into the town. The Royalists attempted to make a stand in the market square, but they were quickly overwhelmed, Colonel Sinnott being among those killed. As at Drogheda, Cromwell and his officers made no attempt to restrain the soldiers, who slaughtered the defenders and citizens of Wexford alike and plundered the town. Hundreds of civilians were shot or drowned as they tried to escape the carnage by fleeing across the River Slaney. Cromwell expressed no remorse for the massacre in his report to Parliament. He justified it as a reward for Sinnott’s intransigience during the negotiations and regarded it as a judgment upon the perpetrators of the Catholic uprising of 1641 and upon the pirates who had operated out of Wexford harbour. His principal regret was that the town was so badly damaged that it was no longer suitable as winter quarters for the Parliamentarian army. The loss of Wexford was a major blow to the Royalist-Confederate coalition. Around 2,000 Royalist soldiers were killed or fled, reducing Ormond's field army to less than 3,000 men, for the loss of between twenty and thirty Parliamentarians. Cromwell captured ships, artillery, ammunition and tons of supplies and a harbour to be used as a naval base in southern Ireland where further supplies from southern England could be received. The Irish privateering fleet was broken up, leaving Prince Rupert's small squadron at Kinsale as the only potential threat to Cromwell's ships and supply lines. Shortly after the fall of Wexford, Rupert broke out of Kinsale and escaped to Portugal. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Oct 13, 2012 23:04:49 GMT

Battle of Faughart

Co. Louth

14th October 1318 Also known as the Battle of Dundalk, it was fought on October 14th 1318. It was a battle of the War of Scottish Independence and the Irish Bruce Wars. Robert Bruce, you’ll remember him as the conniving back-stabber from Braveheart, had defeated the English army of Edward II (the gay Prince of Wales) in 1314. However the gay Prince of Wales, now the gay King of England, like all those psychotic Anglo-Norman bstards never knew when to call it a day and the war was still ongoing, if at a stalemate. Robert, now King of the Scots, decided to open a second front in Ireland. To this end he sent letters and emissaries to the Gaelic chieftains of Ulster calling for a pan-Celtic alliance against the Sassenach and so on. Whenever you get someone suggesting a bad idea like subprime mortgage lending or going to war with the Brits, you’ll always get a taker. In 1315 it was Domhnal O'Neil, king of Tyrone, who took up Bruce’s offer and offering in return the High Kingship of Ireland to Robert’s brother, Edward Bruce. The fact that Domhnal didn’t have any say in who became High King seemed irrelevant. Edward, you’ll recall, landed with a Scottish army at Larne in 1315 and was joined by a number of local chieftains. They had some early successes against the Norman-Anglo-Irish aristocracy. Bruce won his first engagement at Moyry Pass and sacked Dundalk on 29th June. He defeated Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster at the Battle of Connor in Antrim on 10th September. De Burgh was actually Robert Bruce’s father in law so they were keeping it in the family so to speak. On 1st Feb 1316 he defeated Edmund Butler, Justiciar of Ireland, at the Battle of Skerries. Edward Bruce was crowned High King of Ireland on 2nd May 1316. The Kingship was all pie in the sky however. His writ ran only in Ulster. In addition, the weather in 1316 was bad and the harvest failed. The peasants were starving and Bruce’s lads had to rob them of their food to support the army. Things picked up in 1318 and following the harvest Bruce decided to march south and kill a few more Englishmen. He marched through the Moyry Pass which was the only road out of south east Ulster and ended up on Faughart Hill near Dundalk facing an English host marching north. The Ulstermen were a tad nervous at the sight of the English army so Bruce placed them at the top of the hill with his 2,000 Scottish troops in the front line. Edward was supposed to have marched south without waiting for reinforcement from Scotland. If he did, he paid the price. The English forces were led by John de Birmingham, Edmund Butler and Roland Joyce, Archbishop of Armagh. According to Medieval accounts the Scots attacked the English in three columns which were too far apart to be able to support each other. The English defeated the Scots piecemeal. Bruce himslef fell in the battle and he was beheaded, his head being sent to Edward in London and his body interred in Faughart graveyard where a stone slab reputedly marks his burial place. The Scots-Ulster army was dispersed with unknown casualties. Carrickfergus Castle was recaptured on 2nd December by John de Birmingham who was created Earl of Louth by his grateful king. The passing of Edward Bruce was greeted with relief in Ireland. The Annals of Loch Ce noted that Bruce: was the common ruin of the Gaels and Galls of Ireland...never was a better deed done for the Irish than this...For in this Bruce's time, for three years and a half, falsehood and famine and homicide filled the country, and undoubtedly men ate each other in Ireland. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Oct 17, 2012 13:49:04 GMT

The First Cromwellian Siege of Duncannon

Co. Wexford

15th October - 5th November 1649 Google Earth view of Duncannon Fort today and inset map of area Immediately after the fall of Wexford, Cromwell moved to capture the city and port of Waterford. As part of the effort to capture the city, the fort at Duncannon was besieged from 15th October to 5th November 1649. Duncannon controlled access to Waterford and New Ross from the sea. The Royalists had reinforced the garrison with 120 men under command of a Captain Edward Wogan and the fort successfully resisted the siege against Ireton’s 2,000 besiegers. The final straw was a sally by the defenders on 5th November which captured two siege guns. The Cromwellian campaign had suffered small setbacks elsewhere and had failed to isolate Waterford from the west. With winter coming on the sieges were abandoned until spring. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Oct 19, 2012 9:01:24 GMT

The Fall of New Ross

Co. Wexford

19th October 1649 Immediately after the capture of Wexford, Cromwell turned his attention westwards. He left Col Cooke and his regiment to garrison Wexford and sent Ireton to take Duncannon while he marched to New Ross, arriving there on October 17th. The governor of the town was Gen. Taaffe, the future Earl of Carlingford. Taaffe ignored Cromwell’s call to surrender until the town wall was breached on the 19th and then surrendered the town on condition that the garrison be allowed march away with its arms. Cromwell agreed on condition that the artillery be surrendered and that the practice of Catholicism cease. Taaffe took 2,000 men out of New Ross and joined Ormonde’s field army in Kilkenny. However 500 of his men who were Protestant refused to march with him and defected to the Cromwellians. The Parliamentarians then set to building a pontoon bridge across the River Barrow. This job took 2 weeks, the river being 200 yards wide and swollen from the autumn rain. During this period Cromwell fell ill at New Ross and the campaign was somewhat delayed until he recovered. On the 16th Protestant Army Officers in Cork also switched allegiance and liberated those of their comrades who had been arrested in Youghal the previous month. A regiment was despatched by sea to Cork to take control of the city. Meanwhile political activity continued on other fronts. In Ulster Owen Roe O’Neill agreed an alliance with the Confederate/Royalist faction on October 20th. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Oct 22, 2012 14:00:04 GMT

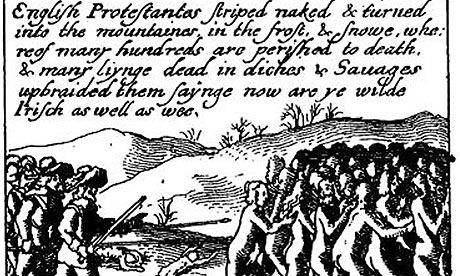

The Rebellion of 1641 The Irish Confederate Wars started in the last week of October 1641, as an attempted coup d'etat by Irish Catholic gentry. The rebellion quickly degenerated into inter-communal violence between the Catholic native Irish and Protestant English and Scottish settlers. The spark that ignited the rebellion was fear of an invasion of Ireland by anti-Catholic English Parliamentarian forces and Scottish Covenanters. Of course the Catholic support for Charles I led English and Scottish Protestants to fear a Papist resurgance and helped to trigger the start of the English Civil War. The rebellion broke out in the last week of October 1641 and was followed months of vilence in Ireland until the Catholic upper classes and clergy formed the Catholic Confederation in the summer of 1642. The Confederation became a de facto government of most of Ireland, independent of the English State but loosely aligned with the Royalist side in the civil wars that became known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The Confederate Wars continued in Ireland until the 1650s and the reconquest of the country by Cromwell and the New Model Army. The roots of the rebellion lie in the failure of the English to assimilate the Irish upper class following the Elizabethan conquest and the plantation of the country. The Irish population was divided into the Old Irish and the Old English (descendants of medieval Norman settlers). These groups were historically antagonistic, with English enclaves around Dublin and other walled towns being fortified against the Gaelic clans. However by Elizabethan times the dividing lines between these groups, especially at the aristocracy level, were becoming blurred. Many Old English lords spoke Irish, patronised Irish poetry and music and intermarried with the Old Irish. Moreover, in the wake of the Reformation, the Old and New Irish were united by their shared religion, Roman Catholicism. The new outsiders were the Church of England and Church of Scotland settlers. From the end of the Elizabethan wars in 1603 to the outbreak of the rebellion in 1641, the political position of the landed Irish Catholics was increasingly threatened by the Protestant English government in Ireland. Protestantism was the only legally approved form of worship in Ireland as in England. Non-attendance at Protestant services was punishable by "recusant fines" and the public practice of Catholicism could lead to arrest. Catholics could not hold senior offices of state, or serve above a certain rank in the army. The Irish privy council and the Irish House of Commons were dominated by Protestants Indeed the Irish Parliament was subordinate to the English Parliament under Poynings' Law. The Protestant administration took every opportunity to confiscate Catholic land. By the late 1630s Thomas Wentworth, Charles I’s representative in Ireland was planning a new round of plantations in Roscommon, Sligo, Galway and Kilkenny. The losers were mainly the "Old English" families. All the while the Catholic aristocracy had been negotiating with the monarchy for the return of their rights and toleration of religion. It never came to pass. Economics also played its part in the outbreak of the rebellion. Interest rates in the 1630s had reached 30% per annum. The economy was in recession and the harvest had failed in 1641. Many of the leaders of the rebellion, men like Phelim O'Neill and Rory O'Moore, were heavily in debt and were in danger of losing their land. The peasants were starving and faced with rising rents. The easy option for them was to kill the landlord. Finally the Irish feared invasion. In 1638 the Scots rose in a revolt (called The Bishops' Wars) against Charles I's attempt to impose Anglicanism in Scotland. They thought it too close to Catholicism for comfort. The King's attempt to put down the rebellion failed when Parliament refused to vote in 1641 for new taxes to pay for raising an army. Charles started negotiations to recruit an Irish army to put down the rebellion in Scotland. During the early part of 1641, some Scots and Parliamentarians proposed invading Ireland to ensure that no royalist Irish Catholic army would invade England or Scotland. A small group of Irish Catholic landowners in turn formulated a plan to take Dublin and other towns around the country in a coup in the name of the King. The Rebellion The planners of the rebellion were a small group of mainly Old Irish, Ulster landowners, Hugh MacMahon and Conor Maguire were to seize Dublin Castle, while Phelim O’Neill and Rory O’Moore were to take Derry and other northern towns. The coup was planned for the 23rd of October 1641. The plan was a surprise attack to take their objectives in the expectation of support from the rest of the country. However the plan was betrayed by an informer, one Owen O’Connolly. Maguire and MacMahon were arrested. O'Neill however successfully took several forts in the north of the country, claiming to be acting in the King's name. The authorities in Dublin reacted quickly and brutally. Fearing that the Catholics planned a massacre of every Protestant in the country they sent troops under command of Charles Coote and William St Leger to rebel held areas in Wicklow and Cork in early 1642. Coote and St Leger did more to provoke a general rebellion that they did to put it down. The rebellion in Munster has been largely attributed to St Leger. in Ulster, the breakdown of state authority prompted widespread attacks by the native Irish on the English Protestant settlers, the Scottish settlers initially were not attacked by the rebels but eventually they too became targets. Insurgent leaders tried to stop the attacks on the settlers, but were unable to control the peasants. In addition many Irish Catholic lords who had lost lands or feared dispossession joined the rebellion and participated in the attacks on the settlers. However, at this stage, the attacks usually involved beating and robbery rather than the killing of Protestants. By early 1642, there were four main concentrations of rebel forces. In Ulster under Phelim O'Neill, around Dublin led by Viscount Gormanstown, in the south east, led by the Butler family, notably Lord Mountgarret and in the south west, led by Donagh MacCarthy, Viscount Muskerry. In areas where British settlers were concentrated, around Cork, Dublin, Carrickfergus and Derry, they had raised their own militia and managed to hold off the rebel forces. Charles I was initially hostile to the rebels and sent a large army to Dublin to put down the rebels. The Scottish parliament also sent an army to Ulster to defend their compatriots there. The Irish rebels were saved by another rebellion, the outbreak of Civil War in England. In part Parliament did not trust Charles with command of the army raised to send to Ireland, fearing that it would afterwards be used against them. Because of th ewar in England, the English troops were withdrawn from Ireland. This gave the Irish Catholics breathing space to create the Catholic Confederation, which would run the Irish war effort. This was instigated by the Catholic clergy and by men like Viscount Gormanstown and Lord Mountgarret. By the summer of 1642, the rebellion proper was over and was superseded by a conventional war between the Irish, who controlled two thirds of the country, and the British-controlled enclaves in Ulster, Dublin and around Cork in Munster. The following period is known as Confederate Ireland. The Confederation sided with the Royalists in return for the promise of self-government and full rights for Catholics after the war. They were finally defeated by Cromwell and the English Parliament's New Model Army from 1649 through to 1653. Massacres The number of planters killed in the early months of the uprising is uncertain. English Parliamentarian pamphlets claimed that over 200,000 settlers had lost their lives though recent research indicates that the number is in the region of 4,000 killed and thousands more ethnically cleansed. It is estimated that up to 12,000 Protestants may have lost their lives in total, the majority dying of cold or disease after being expelled from their homes in the depths of winter. The attacks intensified the longer the rebellion went on. At first, there were beatings and robbing of local settlers, then house burnings and expulsions and finally killings, most of them concentrated in Ulster. The violence escalated after a failed rebel assault on Lisnagarvey in November 1641 during which the settlers killed several hundred captured insurgents. After this battle the massacre of planters in Portadown took place. At Portadown, the Irish soldiers were said by to be led by either Captain Manus O'Cane or Toole McCann. Accounts of the event differed on who participated. In mid November the English inhabitants of the town were rounded up and imprisoned in the Church. Told they were being taken to a ship to be sent to England, they were marched to a bridge over the river Bann. Once on the bridge, they were fmade to strip naked and were then herded into the river at swordpoint where most drowned or died of exposure. Those who loked like escaping were shot by musket-fire. Estimates of the number killed varied from less than 100 to over 300. William Clark, a survivor, said that 100 were killed at the bridge. Other notable massacres in Ulster took place in Kilmore parish where English and Scottish men, women and children were burned to death in the cottage in which they were imprisoned., In County Armagh about 1,250 Protestants were killed in the early months of the rebellion. In County Tyrone the worst massacre took place in Kinard. The killings of Protestant settlers in 1641 is preserved in Loyalist folk memory to this day. Of course the massacres weren’t all one sided and the Protestants took any opportunity presented them for revenge. After a skirmish at Kilwarlin woods near Newry Irish prisoners were executed. The following day English soldiers entered Newry and captured its castle. After the surrender Catholic soldiers and local merchants were lined up on the banks of the river and butchered. On Rathlin Island Scottish Covenanter soldiers of the Argyll's Foot killed hundreds the local Catholic MacDonalds, relatives of their Clan enemy in the Scottish Highlands. Scores of MacDonald women were thrown over the island’s cliffs. Again the number of victims is disputed as being from 100 to as high as 3,000. The widespread killing of civilians was brought under control in 1642, when Owen Roe O'Neill arrived in Ulster from Spain to command the Irish Catholic forces. He hanged several rebels for attacks on civilians. |

|

|

|

Post by groundhog on Oct 24, 2012 23:39:51 GMT

The Battle of Meelick Island Fought on 25th October 1650 as part of the Confederate Wars. Meelick Island is in the River Shannon between Counties Offaly and Galway a few miles south of Banagher.  The area today. Some of the narrow channels are 19th century man-made waterways The Parliamentarians advance on Athlone By October 1650, the Parliamentarian army had captured almost all the Irish strongholds in Ulster, Leinster and Munster. Connacht, protected by the Shannon, had so far remained safe from Cromwellian attack. By this time also Cromwell had returned to England leaving his son-in-law, General Henry Ireton in command. By August Ireton was ready to move against Connacht and the fortifications along the Shannon crossings. Limerick was the last Irish stronghold in Munster and one of the strongest fortresses in the country. Hugh Dubh O'Neill (the hero of Clonmel) had been appointed governor of Limerick but the garrison wasn’t ready for a siege. Oddly, Ireton did not move to attack Limerick with his main army. On 16th August 1650, Ireton sent Sir Hardress Waller with a column to cover the eastern approaches to Limerick. He, himself, set off with his main force to Athlone but he took the scenic route through Counties Carlow and Wicklow. He planned to rendezvous before Athlone with Sir Charles Coote, who was advancing south from Ulster. You will remember that Coote was sent north after Drogheda the previous autumn. The circuitous approach to Athlone was to allow Ireton’s forces to hunt down Irish "tories" operating in County Wicklow. Tories, from the Irish word tóraidhe a hunted man or outlaw, were former Confederate soldiers who raided English-held areas and operated as guerillas. While his main force marched to Naas, Ireton led a column of eight hundred men into the Wicklow mountains, seizing livestock and killing any armed Irishmen that could be found, while smaller detachments raided deep into the Wicklow glens and bogs. Ireton spent several weeks campaigning against the Wicklow tories and did not arrive to meet Sir Charles Coote at Athlone until 16th September. From Athlone Ireton’s plan was to march down the western bank of the Shannon so that Limerick could be attacked from both sides of the river. Ireton believed that Lord Dillon, the Irish commander at Athlone, was planning to surrender the town (with its bridge over the Shannon) to the English in exchange for money and a guarantee of personal safety. However, Dillon had no intention of surrendering Athlone. The deception was intended to draw Ireton away from Limerick to give O'Neill time to prepare its defences. Lord Dillon had destroyed the part of Athlone on the eastern side of the Shannon and withdrawn his troops to the western side where Athlone Castle overlooked the bridge across the river. Lacking heavy artillery to attack the fortifications, Ireton spent two weeks before Athlone waiting in vain for Dillon to surrender the bridge and castle. Finally, he decided to leave Coote and his troops at Athlone while he marched down the eastern side of the Shannon to join Sir Hardress Waller at Limerick. On the march south, Ireton's forces captured a number of Irish outposts in Offaly and Tipperary and posted garrisons near fording sites over the Shannon as a precaution against Irish raids from Connacht. Ireton arrived at Limerick on 6th October. However the garrison was by now fully supplied and prepared for a long siege. Ireton’s summons to Hugh O'Neill to surrender was refused and with the opportunity for a quick end to the siege lost and with winter closing in, Ireton decided to send his army into winter quarters and to make preparations for a determined assault on Limerick in the spring. The English army withdrew from Limerick on 19th October, leaving a covering force on the eastern side of the Shannon to guard against possible Irish incursions into Munster or Leinster. Confederate reaction The man in Comand in Connacht was Ulick Burke, Marquis of Clanricarde. (We met one of his ancestors, another Ulick, at Knockdoe). Clanricarde had been the leading Irish commander in Connacht since 1641 and was widely regarded as the likely successor to the Marquis of Ormond as Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland. The English threat to Connacht during the summer of 1650 galvanised Clanricarde into action. He mustered 3,000 men to support the garrison at Athlone. They however were not needed in the town when Ireton marched south at the end of September. Clanricarde then launched an attack across the River Shannon, with the intention of cutting English communications between Athlone and Limerick and disrupting supply lines through the midlands. In early October, Clanricarde's forces crossed the Shannon at fords around Shannonbridge south of Athlone. Several outposts were overrun as the Irish advanced into English-held territory in western Leinster. Colonel Axtell, the English commander in the area, fell back to Birr and then to Roscrea. Clanricarde gathered reinforcements to bring the strength of his army up to around 4,000 infantry and 500 cavalry. English reinforcements marched up from Wexford and Kilkenny to join Axtell at Roscrea on 21st October. Axtell advanced towards Birr and Clanricarde decided to withdraw and to take up a defensive position at Meelick Island on the River Shannon. The Battle of Meelick Island Soldiers were posted to overlook the ford that the English would have to cross in order to attack the Irish entrenchments on Meelick Island. Despite being heavily outnumbered, Axtell launched a surprise attack late in the evening of 25th October, as darkness began to fall. In fierce hand-to-hand fighting, the Irish were driven back from the ford and Axtell's men advanced onto the island. The speed and ferocity of the English attack overwhelmed the Irish and the whole army was routed. Up to 1,000 Irishmen were killed in the fighting or drowned as they tried to escape across the Shannon in the dark. Although Clanricarde escaped, his personal wagons and tents were captured along with the weapons, horses and the entire baggage train of the Irish army. All the garrsions taken by the Irish on the eastern side of the Shannon were quickly recaptured. Axtell was later court-martialled by Ireton for killing prisoners taken at Meelick after promise of quarter. Around 900 Confederate soldiers died in the battle. |

|