The Battle of Calann

24th July 1261

I have taken this text straight from an online article riginally published in 1961. I'm on holiday at the moment and will edit it when I get home next week.

mccarthy.montana.com/Articles/BattleOfCallann.htmlThis year marks the 7th centenary of a battle which, though often overlooked in history text-books of the shorter type, proved to be one of the most decisive battles to occur in the first century of Norman occupation and in fact, can be said to have set the pattern of history in south-west Munster for three hundred years.

To understand the causes and effects of the Battle of Callann,1 it will be necessary to review briefly the events of the previous century or more. In the 11th century, the peoples inhabiting south Munster were known by the general term Desmumu, the foremost group being the UÍ Echach (later represented by the O'Mahonys). These were displaced by the leading family of Eoghanacht Caisil, the MacCarthys, who from 1118 A.D. onwards, are represented as kings of Desmumu. The reigning king at the time of the Norman invasion was Dermot MacCarthy, who, in 1171 A.D. came to Waterford to submit to King Henry.

If Dermot,2 in submitting to the 'son of the empress,' did so under the impression that Henry would (in the Irish manner) protect him from powerful neighbours, in particular from Henry's own barons, he was very much mistaken. In 1177 Henry made a grant of Dermot's entire kingdom--which he styled the kingdom of Cork--to two of his leading adventurer knights, Robert fitz Stephen and Milo de Cogan.3 The boundaries of this kingdom were St. Brendan's head on the west, Limerick (i.e. the kingdom of Limerick) on the North, the Blackwater near Lismore on the east, and the sea on the south. Using modern terms, it included all south Kerry with the Dingle peninsula, and all Co. Cork plus a portion of south Limerick4 and west Waterford.

According to Giraldus,5 the grantees took possession of seven cantreds only, three to the east of Cork city going to fitz Stephen and four to the west to de Cogan. The remaining twenty four cantreds they allowed to Mac Carthy at rent. Monastic grants and other documents prove conclusively that the two grantees did take possession of lands east and west of the city; needless to say, their ownership of the remainder of the kingdom was purely nominal. Milo de Cogan was slain in 1182 leaving an only daughter, Margaret, while fitz Stephen left no legitimate heir. Further, it appears that Margaret de Cogan was married three times. All these factors helped to confuse the issue of the inheritance, with the result that when King John came to the throne determined to weaken the power of the Irish barons, he found little difficulty in revoking the entire grant and sequestrating to the crown the kingdom of Cork.6 This he proceeded to parcel out among his loyal subjects. In 1200 he granted Eoghanacht Locha Lé7 to Meyler fitz Henry, to hold of the king 'in capite.' Seven years later Philip de Prendergast and Robert fitz Martin were granted lands east of Cork, David de Rupe got the cantred of Rosselithir, while Richard de Cogan (son of Milo's brother, Richard) got Múscraighe Mittaine, which embraced the present baronies of east and west Muskerry and Barrett's.8 These grantees were, of course, expected to win their lands by the sword; fitz Martin and David de Rupe do not appear to have made any impression, but Richard de Cogan and Philip de Prendergast made various settlements, not without some conflict.

Indeed right from the time of the Norman invasion, constant references to warfare between the invaders and the invaded are to be found in the two Munster compilations, the Annals of Innisfallen9 and Mac Carthaigh's Book.10 In 117311 the Normans under Strongbow plundered Lismore completely. An expedition from Dublin raided north Cork in 1176 and Dermot Mac Carthy made peace with them. The following year came the invasion by Milo de Cogan and fitz Stephen, accompanied incidentally, by 'great warfare between Tuadmumu and Desmumu.' It was this dissension amongst the Gaedhil, and in particular amongst the Mac Carthys themselves, that opened the door to the Norman conquest.

However, Domhnall Mór (son of Dermot) who succeeded his father in 1185, did not yield readily. In 1190 the 'grey foreigners' penetrated as far west as Durrus, but were repulsed by the Desmumu. In 1192 they built many castles 'against the men of Munster.' This system of warfare by incastellation was one which the Irish clans neither practised nor understood. In 1195 Cathal Crobderg, king of Connacht, destroyed many of the Munster castles, but they were soon rebuilt, and Cathal came no more. In 1196 Domhnall Mac Carthy attacked Kilfeakle castle12 and destroyed the castles of Imokilly. These included Dún Cuireda,13 In Cora,14 and Mag Ua Mairgili.15 He also destroyed the castle of Lismore16. This provoked retaliatory attacks, first on Férdruim (in Ivagha), where the foreigners were defeated and repulsed,17 and then on Durrus. Castles were built at Ardpatrick and Askeaton, and in 1199 'there was great warfare by the foreigners against Desmumu, and from the Shannon to Férdruim was devastated as a result.'

So went on the ebb and flow of conquest, until in 1211 an attempt was made, supported by the Normans, to depose Diarmaid son of Domhnall mór, and to put Cormac Liathánach II in his place. Diarmaid appears to have got support from the Galls of Cork, and the attempt was unsuccessful.18 The resulting period of strife, however, gave the Normans the opportunity they had been awaiting. Mac Carthaigh's Book19 states that in A.D. 1214:

A castle was built by Mac Cuidithi in Muinntear Bháire, and one at Dún na mBarc by Carew,20 and another at Ard Tuilithe. Another castle by the son of Thomas21 at Dún Lóith, and one at Killorglin. A castle by Roche at Airbhileach.22 A castle by the son of Maurice23 at Magh Uí Fhlaithimh [Moylahiff]. A castle by the son of Sleimhne24 in Corca Laoighdhe.25 A castle by Barrett in the village above Cuan Dor26 [Glandore]. A castle by Nicholas Buidhe [de Barry] at Timoleague.27 And it was during the war of Diarmaid Dúna Droighnein and Cormac Liathánach that the Galls overran the whole of Munster in every direction, from the Shannon to the sea.

Diarmaid fought back, and in 1219 captured a castle at Timoleague.28 Two years later, Geoffrey de Marisco, the Justiciar, brought a hosting into Desmumu, encamping at Áth na h-Uamha (Athnowen or Ovens), destroying the corn crop of the whole country, and building the castle of Magh Rátha (Murragh). This expedition was probably in aid of Richard de Cogan, who does not seem to have followed up his grant on 1207 until some years later. Muscraighe Mittaine, the subject of his grant, embraced a large area stretching from Ballincollig and Mourne Abbey in the east along both sides of the Lee to the Kerry border in the west. During the period up to the battle of Callann, the Cogans conquered most of this area, building castles at Mourne Abbey, Maglin (near Ballincollig), Dundrinan, (Castlemore near Cookstown), Dooniskey, Mahallagh, and Macroom. About 1242 John de Cogan (Richard's son) had the patronage of the churches of Clondrohid, Matehy, and Kilshannig.29 In 1254-5 A.D., "Muscryemychene" was one of the cantreds to pay a compotum of 40/- so that the county sessions might be held there.30

Diarmaid Mac Carthy remained inimical to the Cogans up to the time of his death in 1229; in fact, Dún Droighnein, the site of a Cogan castle, was the place of his death and the place that gave him his cognomen.

Dissensions which broke out amongst the Mac Carthys in 1232-3 may have contributed to their being routed at Tralee in 1234, where Diarmaid, son of Cormac Liathánach, and two of the O'Driscolls were slain. Cormac had two other sons, both called Domhnall; one was known as Domhnall Ruadh, while the other was called Domhnall Gall--appropriately, seeing that on the death of his father in 1244, he handed over Domhnall Ruadh to the Gaill, represented by John fitz Thomas, who promptly put him to death.

The king of Desmond at this time was Cormac Fionn (Diarmaid's brother), who died in his own encampment at Mashanaglass in 1247. This shows that the Cogans were either unable to eject him from Muskerry or, possibly, that he was on friendly terms with them. Not so Finghin, son of Diarmaid Dúna Droighnein, who in 1248 captured Geoffrey de Cogan and drowned him with a stone tied to his neck. The following year he 'made war and wrought great havoc on the Galls of Desmond.'31 But the Cogans, aided by a new ally, Domhnall Cairbreach MacCarthy, 32 slew Finghin. Two years later this Domhnall was in turn taken prisoner and slain by John fitz Thomas and his son Maurice. This no doubt angered the Cogans, who continued to support the Carbery branch of the MacCarthys, and appear to have given no assistance to the Geraldines in their efforts to overthrow the son of Domhnall Cairbreach at Callann.33

The Geraldines were the most prominent of the Norman families of the invasion period and it was inevitable that they should take an interest in the disposing of Desmond. The Irish Pipe Roll of the 14th year of King John34 (1212-1213 A.D.) lists as owing services for the kingdom of Cork, firstly, Thomas Bloet (who the previous year had married the grand-daughter of Milo de Cogan and paid 500 marks for Milo's inheritance)35 and, secondly, Thomas fitz Maurice (of Shanid) whose claim must have rested on his kinship to Raymond le Gros,36 who was, according to Giraldus, fitz Stephen's heir. The claim was not a strong one, and it was by another means that the Geraldines got their foothold in Desmond. On 3 July 1215, King John granted to Thomas fitz Anthony (the earl marshall's seneschal in Leinster) the guardianship (custodia) of Decies and Desmond with all the escheats therein.37 He also granted him the custody of the lands and heir of Thomas fitz Maurice, as well as the marriage of the heir38 (i.e. John fitz Thomas) whom we later find, not surprisingly, married to one of fitz Anthony's daughters. As fitz Anthony had no son, his inheritance descended to his five daughters, one of whom died unmarried, while the four others had as husbands Gerald de Rupe (head of the Roches), Geoffrey de Norrach, Stephen de Archedecne, and John fitz Thomas.39

Was it, in fact, this grant to fitz Anthony which led to the incastellation of Desmond quoted above from Mac Carthaigh's Book?40 At least three of the castle-builders there mentioned may have been sons-in-law of fitz Anthony, namely (John) fitz Thomas, (Gerald) Roche, and Mac Cuidithe, a puzzling name which Orpen41 surmises to have been an early form of Mac Odo, i.e. (Stephen) Archdeacon.

It was easy, in the confused circumstances of the inheritance of the kingdom of Cork, to treat the 'custodia' as if it were a complete grand of ownership. This fitz Anthony and his sons-in-law proceeded to do, aided and abetted by the then Justiciar, Geoffrey de Marisco (who was married to the widow of fitz Thomas' uncle),42 with the result that in 1223 a new Justiciar was ordered to take into the king's hand the 'custodia' of Cork, Decies, and Desmond, as fitz Anthony was treating escheats there as his own, instead of the king's, property.43

Fitz Anthony appears to have been let off on this occasion, but four years later a similar order was given and carried out.44 The new custodian, Richard de Burgh, found so much land alienated by fitz Anthony that there remained not enough to pay the services due to the king.45 Yet fitz Anthony's claims were still recognised. In 1229 de Burgh was allowed 125 of the 250 marks which he yearly rendered the king out of the lands of Thomas fitz Anthony seized by the king's order.46 On fitz Anthony's death in the same year, de Burgh received a mandate to take into the king's hand all lands whereof Thomas fitz Anthony was seised at his death;47 the following year the heirs complained that the justiciar was still distraining them for the debt on fitz Anthony's lands, though they held no part of them.48 Probably by then his sons-in-law were so firmly entrenched that it was impracticable to dislodge them. In 1237, the justiciar was directed that if the lands of Decies and Desmond, which belonged to Thomas fitz Anthony, were in the king's hand, he should not distrain Stephen le Archdekne (son-in-law to Thomas) for debts due by Thomas to the king.49

But John fitz Thomas was the one who came to the forefront in these dealings. In 1244 he was granted free chase and warren in Okonyl, Muskry, Kery, Yomach, and Orathat50 while in 1251 he was granted £25 a year in compensation for his portion of Decies.51

What happened next is incidentally related in an inquisition on the lands of John de Prendergast of Ardnesylach, A.D. 1278.52 It appears that three of fitz Anthony's sons-in-law--Gerald, Geoffrey, and Stephen--opposed the king in the war of Kildare53 and could not therefore obtain pardon for their lands; but John fitz Thomas sided with the king. He afterwards crossed over twice or three times to Lord Edward seeking all the lands for 500 (marks or pounds) per annum. Finally (in 1259) Edward enfeoffed John for that rent,54 but Stephen de Longespée, then justiciar of Ireland, saying that John had deceived Lord Edward, refused to give him seisin. John thereupon proceeded to take possession without the justiciar's consent; after that the barons of the exchequer refused to accept rent for the lands 'because he never had seisin by the said justiciary or other bailiffs of the Lord Edward in Ireland.'

In the event, John's hard-won charter was to prove his death-warrant, leading, as it did, to a new onslaught on the MacCarthys, culminating in the battle of Callann. Already, in 1252, he had slain Domhnall Got Cairbreach (ally of the Cogans) who had taken the kingship of Desmond after the death of his brother, Cormac Fionn. But Domhnall's eldest son, Finghin, was to emerge as an even more troublesome opponent. First (in 1253) he attacked Geoffrey O'Donoghue, whose wife (Sadhbh O'Brien) was suspected of having betrayed Domhnall Got to fitz Thomas. Both Geoffrey and Sadhbh, as well as others of the family, were slain. Next (1258), he attacked and slew several of the O'Mahonys. In 1260 he raided Ciarraighe (Luachra) at the head of the Desmumu, 'and great conflagrations were there caused by them.' The same year Eoghan O Muircheartaigh was slain by foreigners at Dún na mBarc; Mac Carthy avenged his death the year after by burning not alone Dún na mBarc, but also Dún Uabhair,55 Caisleán na Gidhi,56 and Innishannon.

It was clear to fitz Thomas that if these insolent forays were not suppressed his grant would be valueless. But, having antagonised the forces of officialdom in Ireland, he stood little chance of being aided by the king's army in his assault on Desmond. Fortunately for him, Stephen de Longespée died in 1260, being replaced as justiciar by William de Dene. The new justiciar must have been better disposed towards John and his ambitions, as it did not take long to induce him to lead the feudal forces into Desmond. To obviate objections on the score of finance, fitz Thomas and other barons of Desmond underwrote the expenses involved.57

The Munster Geraldines formed the backbone of the expedition,58 headed by the redoubtable John fitz Thomas and his son, Maurice fitz John. Another of the Norman leaders was 'the son of Richard,'59--probably Walter de Burgo, lord of Connacht and later earl of Ulster, whose father's highly-successful Connacht invasion of 1235 fitz Thomas no doubt expected to emulate. Of the Irish, they had Domhnall Ruadh, a son of Cormac Fionn and a strong claimant to the kingship of Desmond; he had with him 'all the Irish he could get.'60

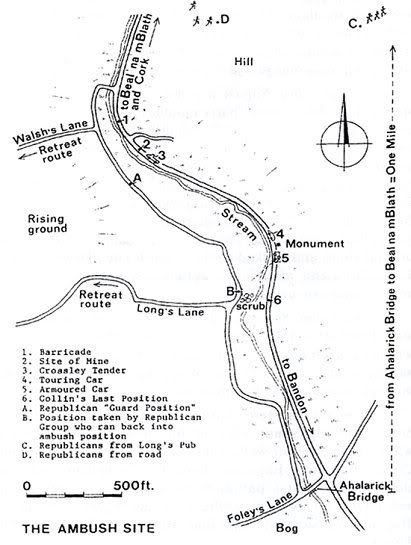

But Finghin Mac Carthy had learned much from his opponents during his years of conflict, while he had the added advantage of knowing intimately the territory over which he fought. At Callann he chose his battleground, at a spot where a mountainy river called the Slaheny joins the Ruachtach,61 close by the castle of Ardtully. No doubt he reckoned that here the heavily-armoured cavalry of the invader could be used to the least advantage.

Battle was then62 joined and Finghin mac Domhnaill mhic Charthaigh emerged victorious.

Unfortunately no details of the conflict, --apart from the names of those slain--are available. Incidentally, the fullest account of the battle is given, not by the Munster annals, but by the Annals of Loch Ce and Annals of Connacht:

A.D. 1261. A great war and numerous injuries were committed in this year by Finghin, son of Domhnall Mac Carthaigh and his brothers, against the foreigners. There was a great hosting by the Geraldines into Desmond to attack Mac Carthy, but it was Mac Carthy attacked them, and defeated them. There were killed there the son of Thomas (John was his own name), his son, and fifteen knights along with them. Eight good barons were also slain with many squires and soldiers (sersénaigh) innumerable.63

The loss of the head of the Munster Geraldines and his heir64 was not the most grievous blow the Normans suffered. Worse still was the loss of prestige occasioned by the magnitude and conclusiveness of the defeat itself. Little wonder that it marked a turning-point in their fortunes. In the early days of the conquest, their heavily-armed professional soldiers had but to show themselves to strike terror into the hearts of the natives, as did John de Courcy's men when the Ulaidh assembled to attack them at Downpatrick in 1178.65 Indeed, only the year before Callann, another crushing defeat at Downpatrick drew the following poetic lament:

Unequal they came to the battle,

The foreigners and the race of Tara,

Fine linen shirts on the race of Conn,

The foreigners one mass of iron.66

Now, however, Finghin Mac Carthy's lightly-clad Gaedhil had proved themselves the equals of the Normans in battle. The resulting uplift to their morale made itself felt immediately. At the head of the Desmumu, Finghin swept eastwards and northwards through Desmond, burning the Norman strongholds of Dún Mic Oghmainn,67 Dún Uisce,68 Macroom, Magh Oiligh,69 Dunloe, and Killorglin, as well as much of the land of Uí Chonaill.70

'Fasighi imdha i nNessumin' (many wastes in Desmond) the Annals of Innisfallen commented briefly. Not even the Cogan lands in Muskerry escaped, for at least three of the castles mentioned, --Dún Uisce, Macroom, and Magh Oiligh--were on the territory of the Cogans. Finghin spared nobody in his determined efforts to clear everyone of Norman descent out of the once extensive kingdom of his great-grandfather, Dermot Mac Carthy.

He over-reached himself, however. Penetrating eastwards as far as Kinsale, he presented himself before de Courcy's stronghold of Ringrone. Alarmed at his reputation Miles de Courcy offered terms, which Finghin, flushed with victory, rejected. Whereupon Miles, who was a grandson of Milo de Cogan, and probably of John de Courcy as well, marched his full body of troops to Bearnach Reanna Róin71 and there defeated the Irish on the Thursday after Michaelmas. Finghin and many of the nobles of Desmond being slain.72

Thus fell the great Finghin, ever afterwards described as Finghin Reanna Róin.73 After his death his brother, Cormac, took over the chieftainship. Had Finghin been alive, it is unlikely that the new justiciar, Richard de la Rochelle would have been allowed to land at Dún na long and depart unmolested.74 Cormac waited for the next year to show his prowess, when another large expedition headed by Walter de Burgo75 invaded Desmond, presumably to avenge the defeat of Callann. The following is the account given in the Annals of Innisfallen (1262 A.D.):

Mac William de Burgo accompanied by a great army of foreigners and Gaedhil invaded Desmumu, and Cormac Mac Carthaigh was slain by them after a victory of prowess and valour. For he himself unaided, slew Gerald Roche,76 a great and noble knight, and another good squire, and no others of the Desmumu fell save he, although many of the (enemy) army were slain. Nevertheless, some of the Clann Charthaigh gave hostages to Mac William and he left the country.

The account in the Annals of Loch Cé differs slightly from the above:

A.D. 1262. A hosting by Mac William Burk and the foreigners of Erin to Desmumha to attack Mac Carthaigh, until they reached the Mangartach of Loch Léin, where Gerald Roche was slain by Mac Carthaigh; and it was said that he was the third best baron in Ireland. And this was the joy with sorrow to Desmumha, for the son of Domhnall Got Mac Carthaigh, i.e. Cormac, son of Domhnall, was slain on that same day; and the foreigners and the Gaedhil suffered great losses on that day around the Mangartach.77

From these accounts it would seem that while Cormac failed to match Finghin's exploits, the Normans gained little advantage either. It is significant that references to attacks on Desmond scarcely occur at all after 1262.78 It is to this period that Hanmer's often-quoted account refers:79

The Carties plaied the Divells in Desmond, where they burned, spoiled, preyed, and slue many an innocent; they became so strong, and prevailed so mightily that for the space (so it is reported) of twelve yeeres the Desmonds durst not but plow in ground in his owne country.

With the fall of Dunloe and Killorglin, following on the death of fitz Thomas and his heir, the unprotected Geraldine lands in Kerry (i.e. Ciarraighe Luachra) as well as in Desmond were so pillaged that when young Thomas, son of Maurice, came of age in 1282, their value had greatly depreciated.

The inquisition then taken80 relates that John fitz Thomas died seised of 3½ cantreds in Decies, also of shrievalty and sergeancy of Cork and Kerry. He had lands in Acumkery (i.e. Trughanacmy) in the Co. of Kerry, held of Sir Milo de Curcy for the service of two knights. These lands used to be worth £150 in the time of John, but were now worth only £50,81 besides the thirds of the Lady Matilda de Barry, who was the wife of Maurice fitz John, the greater part of which is destroyed by the war of the Irish. He had three carucates at Ogenathy Donechud (i.e. Eoghanacht Uí Dhomhchadha), wont to be worth in time of peace 40 marks, now worth nothing, for they all lie in the power of the Irish, ½ carucate at Corleleye82 of Robert fitz Stephen, worth formerly 40 marks, now 10, as nearly the whole has been destroyed by the war of the Irish; Clonlathtyn and Dromynargyn formerly worth 10 marks, now worth nothing.

A similar state of affairs prevailed in the Cogan lands of Muskerry, as the following account of them, taken in 1281 while the lands were in ward of the king, shows:83

He answers nothing for the lands which Richard de Cogan held in Forgus84 and Stedryth, and for the lands which John Heydrun and the heir of William Russell hold in the manor of Mora (i.e. Mourne Abbey) and for the lands of Clonehyt85 of Dundreynan, and the manor of Newcastle, because they were waste on account of the war of the Irish.

Attempts at subduing the Mac Carthys were of little avail. James de Audley (justiciar from 1270 to 1272) led an expedition against Irish rebels in Desmond86; no results were announced. The Annals of Innisfallen (A.D. 1271) tell us: "A hosting by the foreigners of Ireland into Desmumu to Dún na mBarc, and they turned back from there without doing any further damage."

In 1280 the Mac Carthys of Carbery (then headed by Domhnall óg son of Domhnall Mael) made peace with the main branch of the family, whose king was Domhnall Ruadh mac Carthy,87 and they apportioned Desmond amongst themselves. They then united to drive out the foreigner. Killorglin was burned and its castle razed. 'And great forays were made there and people slain.' The Normans then evacuated Dunloe, which was promptly burned.88

The truce was a brief one. Three years later, Domhnall Ruadh, on the pretext of a plot against himself, made a hosting against the MacCarthys of Carbery. He brought with him the principle foreigners of Ireland, Thomas de Clare, Maurice fitz Maurice, Thomas fitz Maurice (head of the Munster Geraldines), John de Barry, Roches, Condons, etc. They plundered and scattered the men of Carbery.89

Still Domhnall óg (Cairbreach) remained a thorn in the side of the Norman interests. In 1295 he was plundering as far east as Kinalea, having already burned Macloneigh.90 Two years later, he slew John de Courcy, probably to avenge his uncle's death at the hands of Miles de Courcy. When Hubert de Courcy tried to bring Domhnall to justice, the sheriff reported that Domhnall would not submit to justice, and a few months later, that he 'was among the Irish in waste land where no sergeant or bailiff of the king dared to go to attack him.'91

He also gets frequent mention with regard to fines for transgressions, paying £68 on one occasion through John de Cogan.92 That the traditional friendship still existed between the MacCarthys of Carbery and the Cogans is shown by the fact that John de Cogan was a pledge for the appearance of Domhnall óg Cairbreach at a parley concerning restitution to John de Barry.93

As for Domhnall Ruadh, he was now apparently regarded as an independent prince, able to call upon the assistance of Norman barons, and in a position to treat directly with the king. He did not exist in a state of semi-outlawry as did Domhnall óg. In 1284, 'Donald Rufus MacCarthy, lord of the Irish of Desmond' wrote to King Edward vehemently desiring to be subjected to his domination, and sending Brother Walter of Kilkenny as intermediary.94 this overture must have resulted from the coming of age of Thomas fitz Maurice who renewed his claim to the lands of his grandfather (John of Callann). Domhnall followed up his letter with a visit to England in order to safeguard his position.95

Trouble arose again, however, for the expense sheet of the archbishop of Dublin when keeper of Ireland (1288-1290) mentions that when news came that 'Donald Roche' and other Irishmen began to be hostile soon after the justiciar's death, an expedition was deemed necessary. But the route taken led in a straight line from Cork to Limerick (via Mourne Abbey and Buttevant), while a second expedition travelled via Clonmel, Ardfinnan, Castlelyons, Cork and Waterford. The Archbishop must have made some kind of treaty with Domhnall as he got a fine of 50 marks from him.96 Similar fines for transgressions and for having peace were obtained in 1296 from Donald Roth, Finin, Donald óg, and Donat Dermot Feynyn.97

Nevertheless, the decay of Norman rule could not be stopped, and the Mac Carthys were now firmly established as lords of south Kerry and west Cork.98 The Cogans gradually lost their power and lands in Muskerry,--as much from the attacks of Geraldines and Barretts99 as from the encroachments of the Mac Carthys. In the 14th century the viceroys Lionel and Rokeby made efforts to recover Cogan lands from the Mac Carthys in east Muskerry,100 but in 1398 the Mac Carthys were not alone free to plunder from Dingle to the territory of the Barretts, but could carry on their ancient feud against the Carbery Mac Carthys at Carrigrohane, practically at the gates of Cork city.101

As for the Geraldines, though Thomas fitz Maurice did succeed in getting a re-grant of this grandfather's lands in 1292,102 yet their overlordship of the Mac Carthys was but in name, while the rent which they claimed has almost always to be exacted by force. Their exactions being as forcefully resisted, there ensued many bloody conflicts over "the earl's beeves," as well as--despite occasional intermarriages--a bitter enmity, which came to an end only with the fall of the Geraldine house of Desmond in 1582. And then, by the turn of history's wheel, the MacCarthys fought on the side of, and the Fitzgeralds as rebels against, the crown.